README

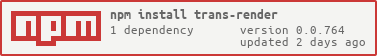

trans-render

trans-rendering (TR) describes a methodical way of instantiating a template. It originally drew inspiration from the (least) popular features of XSLT, but has since evolved to resemble standard CSS. Like XSLT, TR performs transforms on elements by matching tests on those elements. Whereas XSLT uses XPath for its tests, TR uses css path tests via the element.matches() and element.querySelectorAll() methods. Unlike XSLT, though, the transform is defined with JavaScript, adhering to JSON-like declarative constraints as much as possible.

A subset of TR, also described below, is "declarative trans-render" syntax [DTR], which is pure, 100% declarative syntax.

DTR is designed to provide an alternative to the proposed Template Instantiation proposal, the idea being that DTR could continue to supplement what that proposal includes if/when template instantiation support lands in browsers.

XSLT can take pure XML with no formatting instructions as its input. Generally speaking, the XML that XSLT acts on isn't a bunch of semantically meaningless div tags, but rather a nice semantic document, whose intrinsic structure is enough to go on, in order to formulate a "transform" that doesn't feel like a hack.

There is a growing (🎉) list of semantically meaningful native-born DOM Elements which developers can and should utilize, including dialog, datalist, details/summary, popup/tabs (🤞) etc. which can certainly help reduce divitis.

But even more dramatically, with the advent of imported, naturalized custom elements, the ratio between semantically meaningful tag names and divs/spans in the template markup will tend to grow much higher, looking more like XML of yore. trans-render's usefulness grows as a result of the increasingly semantic nature of the template markup. Why? Because often the markup semantics provide enough clues on how to fill in the needed "potholes," like textContent and property setting, without the need for custom markup, like binding attributes. But trans-render is completely extensible, so it can certainly accommodate custom binding attributes by using additional, optional helper libraries.

This can leave the template markup quite pristine, but it does mean that the separation between the template and the binding instructions will tend to require looking in two places, rather than one. And if the template document structure changes, separate adjustments may be needed to keep the binding rules in sync. Much like how separate css style rules often need adjusting when the document structure changes.

The core libraries

This package contains three core libraries.

The first, lib/TR.js, is a tiny, 'non-committal' library that simply allows us to map css matches to user-defined functions, and a little more.

The second, lib/DTR.js, extends TR.js but provides robust declarative syntax support. With the help of "hook like" web component decorators / trans-render plugins, we rarely if ever need to define user-defined functions, and can accomplish full, turing complete (?) rendering support while sticking to 100% declarative JSON.

In addition, this package contains a fairly primitive library for defining custom elements, lib/CE.js, which can be combined with lib/DTR.js via lib/mixins/TemplMgmt.js.

The package xtal-element builds on this package, and the documentation on defining custom elements, with trans-rendering in mind, is documented there [WIP].

So the rest of this document will focus on the trans-rendering aspect, leaving the documentation for xtal-element to fill in the missing details regarding how lib/CE.js works.

value-add by trans-rendering (TR.js)

The first value-add proposition lib/TR.js provides, is it can reduce the amount of imperative *.selectQueryAll().forEach's needed in our code. However, by itself, TR.js is not a complete solution, if you are looking for a robust declarative solution. That will come with the ability to extend TR.js, which DTR.js does, and which is discussed later.

The CSS matching that the core TR.js supports simply does multi-matching for all (custom) DOM elements within the scope, and also scoped sub transforms.

Note that TR.js is a class, with key method signatures allow for alternative syntax / extensions.

Multi-matching

Multi matching provides support for syntax that is convenient for JS development. Syntax like this isn't very pleasant:

"[part*='my-special-section']": {

...

}

... especially when considering how common such queries will be.

So transform.js supports special syntax for css matching that is more convenient for JS developers:

mySpecialSectionParts: {

...

}

Throughout this documentation, we will be referring to the string before the colon as the "LHS" (left-hand-side) expression.

Syntax Example

Example 1

<body>

<template id=Main>

<button data-count=10>Click</button>

<div class="count-wide otherClass"></div>

<vitamin-d></vitamin-d>

<div part="triple-decker j-k-l"></div>

<div id="jan8"></div>

<div -text-content></div>

</template>

<div id=container></div>

<script type="module">

import { TR } from '../../lib/TR.js';

TR.transform(Main, {

match: {

dataCountAttrib: ({target, val}) =>{

target.addEventListener('click', e => {

const newCount = parseInt(e.target.dataset.count) + 1;

e.target.dataset.count = newCount;

transform(container, {

match: {

countWideClasses: ({target}) => {

target.textContent = newCount;

},

vitaminDElements: ({target}) => {

target.textContent = 2 * newCount;

},

tripleDeckerParts: ({target}) => {

target.textContent = 3 * newCount;

},

idAttribs: ({target}) => {

target.textContent = 4 * newCount;

},

textContentProp: 5 * newCount,

'*': ({target, idx}) => {

target.setAttribute('data-idx', idx);

}

}

});

})

}

}

}, container);

</script>

</body>

The keyword "match" indicates that within that block are CSS Matches.

So for example, this:

dataCountAttribs: ({target, val}) => {

...

}

is short-hand for:

fragment.querySelectorAll('[data-count]').forEach(target => {

const val = target.getAttribute('data-count');

...

})

What we also see in this example, is that the transform function can be used for two scenarios:

- Instantiating a template into a target container in the live DOM tree:

tr.transform(Main, {...}, container)

- Updating an existing DOM tree:

tr.transform(container, {...})

We can also start getting a sense of how transforms can be tied to custom element events. Although the example above is hardly declarative, as we create more rules that allow us to update the DOM, and link events to transforms, we will achieve something approaching a declarative yet Turing complete(?) solution.

The following table lists how the LHS is translated into CSS multi-match queries:

| Pattern | Example | Query that is used | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ends with "Parts" | myRegionParts | .querySelectorAll('[part*="my-region"]') | May match more than bargained for when working with multiple parts on the same element. |

| Ends with "Attribs" | ariaLabelAttribs | .querySelectorAll('[aria-label]') | The value of the attribute is put into context: ctx.val |

| Contains Eq, ends with Attribs [TODO] | ariaLabelEqHelloThereAttribs | .querySelectorAll('[arial-label="HelloThere"]) | If space needed ("Hello There") then LHS needs to be wrapped in quotes |

| Ends with "Elements" | flagIconElements | .querySelectorAll('flag-icon') | |

| Ends with "Props" | textContentProps | .querySelectorAll('[-text-content]') | Useful for binding properties in bulk |

| Anything else | 'a[href$=".mp3"]' | .querySelectorAll('a[href$=".mp3"]') |

Nested Matching

Just as CSS will support nesting (hopefully, eventually), TR supports nesting out-of-the-box. If the RHS is a non-array object, a sub transform is performed within that scope (Only one exception -- if using lhs that ends with Props for bulk prop setting).

Extending TR with DTR (Declarative Trans Rendering)

The lib/DTR.js file extends the class in the file TR, and continues to break things down into multiple methods, again allowing for alternative syntax / implementations.

Many of these methods dynamically load modules, so if extending DTR, and overriding these methods, the implementations in those methods impose no penalty.

Declarative trans-render syntax via plugins

Previously, we saw the core value-add that trans-rendering library provides:

Making

dataCountAttribs: ({target, val}) => {

...

}

short-hand for:

fragment.querySelectorAll('[data-count]').forEach(target => {

const val = target.getAttribute('data-count');

...

})

We can make this more declarative, by using the RenderContext's plugin object:

const dataCountPlugin = {

selector: 'dataCountAttribs',

processor: ({target, val}) => {

...

}

}

transform(Main, {

plugins: {

myPlugin: dataCountPlugin

},

match:{

[dataCountPlugin.selector]: 'myPlugin'

}

})

Developing a dynamically loaded be-* plugin

A special class of plugins can be developed with these characteristics:

- Transform is associated with a be-decorated custom attribute / decorator/ behavior, where the attribute starts with be- or data-be-.

- Optionally, if the plugin isn't yet loaded before the transform starts, it can be skipped over, and fall back to the decorator being executed after the library has downloaded (and the cloned template has already been added to the DOM live tree). This allows the user to see the rest of the HTML content without being blocked waiting for the library to download, and apply the plugin once progressively loaded (but DOM manipulation is now a bit costlier, as the browser may need to update the UI that is already visible).

We call such plugins "be-plugins".

To create a be-plugin create a script as follows:

import {RenderContext, TransformPluginSettings} from 'trans-render/lib/types';

import {register} from 'trans-render/lib/pluginMgr.js';

export const trPlugin: TransformPluginSettings = {

selector: 'beMyBehaviorAttribs',

processor: async ({target, val, attrib, host}: RenderContext) => {

...

}

}

register(trPlugin);

We can now reference this be-plugin via a simple string:

transform(Main, {

plugins: {

beMyBehaviorAttribs: true,

},

match:{

}

})

Useful plugins that are available:

- be-plugin for be-observant

- be-plugin for be-repeated

Declarative trans-render syntax via PostMatch Processors

The examples so far have relied heavily on arrow functions. (In the case of plugins, we are, behind the scenes, amending the matches to include additional, hidden arrow functions on the RHS.)

As we've seen, this provides support for 100% no-holds-barred non-declarative code:

const matches = { //TODO: check that this works

details:{

summary: ({target}: RenderContext<HTMLSummaryElement>) => {

///knock yourself out

target.appendChild(document.body);

}

}

}

These arrow functions can return a value. DTR.js has some built-in standard "post match" processors that allow us to "act" based on the data contained on the RHS, including data that might be returned from a arrow function above.

The capabilities of these post-match processors are quite limited in what they can do, due to the small number of expression types JavaScript (and especially JSON) supports.

So we reserve the limited declarative syntax JSON provides for the most common use cases.

The first common use case is setting the textContent of an element, which we lead up to below.

Declarative, dynamic content based on presence of ctx.host

The inspiration for TR came from wanting a syntax for binding templates to a model provided by a hosting custom element.

The RenderContext object "ctx" supports a special placeholder for providing the hosting custom element: ctx.host. But the name "host" can be interpreted a bit loosely. Really, it could be treated as the provider of the model that we want the template to bind to.

But having standardized on a place where the dynamic data we need can be derived from, we can start adding declarative string interpolation:

match:{

"summary": ["hello", "place"]

}

... means "set the textContent of the summary element to "hello [the value of the "place" property of the host element or object]".

Let's look at an example in more detail:

<details id=details>

<summary>Amor Omnia Vincit</summary>

<article></article>

...

</details>

<script type="module">

import { DTR } from 'trans-render/lib/DTR.js';

DTR.transform(details, {

match:{

"summary": ["Hello", "place", ". What a beautiful world you are."],

"article": "mainContent"

},

host:{

place: 'Mars',

mainContent: "Mars is a red planet."

},

});

</script>

The array alternates between static content, and dynamic properties coming from the host.

The binding support for string properties isn't limited to a single property key.

If the property key starts with a ".", then the property key supports a dot-delimited path to a property. And "??" is supported. So:

match:{

"summary": ["Hello ", ".place.location ?? world"],

}

will bind to host.place.location. If that is undefined, then the "world" default will be used. If the string to the right of ?? starts with a ., the same process is repeated recursively.

Ternary expressions are supported:

match:{

"button": "?open - : +"

}

Means "if the host.open property is true, then set the button's textContent to "-", else "+".

If the string to the right of open starts with a "." or a "?", then the same process is repeated recursively.

P[E[A]]

After setting the string value of a node, setting properties, attaching event handlers, and setting attributes (including classes and parts) comes next in things we do over and over again.

So we reserve another of our extremely limited RHS types JSON supports to this use case.

We do that via using an Array for the rhs of a match expression. We interpret that array as a tuple to represent these settings. P stands for Properties, E for events, A for attributes.

Property setting (P)

We follow a similar approach for setting properties as we did with the SplitText plug-in.

The first element of the RHS array is devoted to property setting:

<template id=template>

<my-custom-element></my-custom-element>

</template>

<script type=module>

import { DTR } from 'trans-render/lib/DTR.js';

DTR.transform(template, {

match:{

myCustomElementElements: [{myProp0: ["Some Hardcoded String"], myProp1: "hostPropName", myProp2: ["Some interpolated ", "hostPropNameForText"]}]

},

});

</script>

The same limited support for . and ?? described above is supported here.

Add event listeners

The second element of the array allows us to add event listeners to the element. For example:

match:{

myCustomElementElements: [{}, {click: myEventHandlerFn, mouseover: 'myHostMouseOverFn', 'myProp:onSet': {...}}]

}

As you can see, TR/DTR supports three ways to hookup an event handler. The first one is not JSON serializable, so it doesn't qualify as "declarative". It works best with arrow function properties of the host (no binding attempt is made). Likewise with the second option, but here we are referencing, by name, the event handler from the host.

The third option provides a declarative syntax for doing common things done in an event handler, but declaratively. Things like toggling property values, incrementing counters, etc.

The syntax is borrowed from the be-noticed decorator / DTR plugin, and much of the code is shared between these two systems (WIP).

Set attributes / classes / parts / decorator attributes.

Example:

match:{

myCustomElementElements: [{}, {}, {

myAttr: "myHostProp1",

".my-class": true,

myBoolAttr": true,

myGoAwayAttr: null,

"::my-part": true,

beAllYouCanBe: {

some: "JSON",

object: true,

}}]

}

Boolean RHS -- Remove and Refs

If the RHS is boolean value "false", then the matching elements are removed.

If the RHS is boolean value "true", then the matching elements are placed in the Host element with property key equal to the LHS. This is the "ref" equivalent of other templating libraries. One difference, perhaps, is the property is set to an array of weak references.

[TODO] Show examples

Conditional RHS [TODO]

If the RHS is an array, but the head element of the array is a boolean, then we switch into "conditional display" logic.

| First Element Value | Second Element Usage | Third Element Usage | Fourth Element Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| true | The second element is expected to be an object that matches the [BeSwitchedVirtualProps type](https://github.com/bahrus/be-switched/blob/baseline/types.d.ts#L5). Only the right hand side of many of those field expressions are evaluated recursively from the rules above. | If the second element is satisfied, apply the third element according to all the rules above (recursively), assigning values / attaching event handlers on the target element | If the second element is **not** satisfied, apply the third element according to all the rules above (recursively), assigning values / attaching event handlers on the target element |

| false | "" | If the second elements is satisfied, skip the rest of the transform rules? | tbd |

Inserting Content [TODO]

If the RHS is an array, but the head element of the array is itself an array, then we interpret this to be a template include rule. Follow be-inclusive syntax.

Loops [TODO]

If the RHS is an array, but the head element of the array is the number 0, then the array provides the ability to define a loop

TBD [TODO]

What if first element is null?